“The Lake” by Tananarive Due, tells the story of Abbie LeFleur, a lifetime Bostonian who hides her scales, webbed feet, and an incredible hunger for people. She’s relocated to Graceville to start her life anew when she sets her eyes on a young student in her English class.

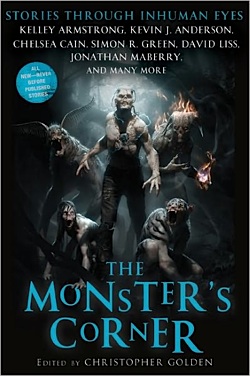

This story is featured in the upcoming monster anthology Monster’s Corner, out from St. Martin’s Press on September 27th. You can download a a free ebook version of this story here or wherever ebooks are sold. Check out who else is gathered in the Monster’s Corner on Facebook.

Keep an eye on Tor.com next week for more monster tales and read what we’re doing in the future for All Hallow’s Read.

The new English instructor at Graceville Prep was chosen with the greatest care, highly recommended by the board of directors at Blake Academy in Boston, where she had an exemplary career for twelve years. There was no history of irregular behavior to presage the summer’s unthinkable events.

—Excerpt from an internal memo Graceville Preparatory School Graceville, Florida

Abbie LaFleur was an outsider, a third-generation Bostonian, so no one warned her about summers in Graceville. She noticed a few significant glances, a hitched eyebrow or two, when she first mentioned to locals that she planned to relocate in June to work a summer term before the start of the school year, but she’d assumed it was because they thought no one in her right mind would move to Florida, even northern Florida, in the wet heat of summer.

In fairness, Abbie LaFleur would have scoffed at their stories as hysteria. Delusion. This was Graceville’s typical experience with newcomers and outsiders, so Graceville had learned to keep its stories to itself.

Abbie thought she had found her dream job in Graceville. A fresh start. Her glasses had fogged up with steam from the rain-drenched tarmac as soon as she stepped off the plane at Tallahassee Airport; her confirmation that she’d embarked on a true adventure, an exploration worthy of Ponce de León’s storied landing at St. Augustine.

Her parents and her best friend, Mary Kay, had warned her not to jump into a real estate purchase until she’d worked in Graceville for at least a year—The whole thing’s so hasty, what if the school’s not a good fit? Who wants to be stuck with a house in the sticks in a depressed market?—but Abbie fell in love with the white lakeside colonial she found listed at one-fifty, for sale by owner. She bought it after a hasty tour—too hasty, it turned out—but at nearly three thousand square feet, this was the biggest house she had ever lived in, with more room than she had furniture for. A place with potential, despite its myriad flaws.

A place, she thought, very much like her.

The built-in bookshelves in the Florida room sagged. (She’d never known that a den could be called a Florida room, but so it was, and so she did.) The floorboards creaked and trembled on the back porch, sodden from summer rainfall. And she would need to lay down new tiles in the kitchen right away, because the brooding mud-brown flooring put her in a bad mood from the time she first fixed her morning coffee.

But there would be boys at the school, strong and tireless boys, who could help her mend what ever needed fixing. In her experience, there were always willing boys.

And then there was the lake! The house was her excuse to buy her piece of the lake and the thin strip of red-brown sand that was a beach in her mind, although it was nearly too narrow for the beach lounger she’d planted like a flag. The water looked murky where it met her little beach, the color of the soil, but in the distance she could see its heart of rich green-blue, like the ocean. The surface bobbed with rings and bubbles from the hidden catfish and brim that occasionally leaped above the surface, damn near daring her to cast a line.

If not for the hordes of mosquitoes that feasted on her legs and whined with urgent grievances, Abbie could have stood with her bare feet in the warm lake water for hours, the house forgotten behind her. The water’s gentle lapping was the meditation her parents and Mary Kay were always prescribing for her, a soothing song.

And the isolation! A gift to be treasured. Her property was bracketed by woods of thin pine, with no other homes within shouting distance. Any spies on her would need binoculars and a reason to spy, since the nearest homes were far across the lake, harmless little doll houses in the anonymous subdivision where some of her students no doubt lived. Her lake might as well be as wide as the Nile, protection from any envious whispers.

As if to prove her newfound freedom, Abbie suddenly climbed out of the tattered jeans she’d been wearing as she unpacked her boxes, whipped off her T-shirt, and draped her clothing neatly across the lounger’s arm rails. Imagine! She was naked in her own backyard. If her neighbors could see her, they would be scandalized already, and she had yet to commence teaching at Graceville Prep.

Abbie wasn’t much of a swimmer—she preferred solid ground beneath her feet even when she was in the water—but with her flip-flops to protect her from unseen rocks, she felt brave enough to wade into the water, inviting its embrace above her knees, her thighs. She felt the water’s gentle kiss between her legs, the massage across her belly, and, finally, a liquid cloak upon her shoulders. The grade was gradual, with no sudden drop-offs to startle her, and for the first time in years Abbie felt truly safe and happy.

That was all Graceville was supposed to be for Abbie LeFleur: new job, new house, new lake, new beginning. For the week before summer school began, Abbie took to swimming behind her house daily, at dusk, safe from the mosquitoes, sinking into her sanctuary.

No one had told her—not the realtor, not the elderly widow she’d only met once when they signed the paperwork at the lawyer’s office downtown, not Graceville Prep’s cheerful headmistress. Even a random first-grader at the grocery store could have told her that one must never, ever go swimming in Graceville’s lakes during the summer. The man-made lakes were fine, but the natural lakes that had once been swampland were to be avoided by children in particular. And women of childbearing age—which Abbie LaFleur still was at thirty-six, albeit barely. And men who were prone to quick tempers or alcohol binges.

Further, one must never, ever swim in Graceville’s lakes in summer without clothing, when crevices and weaknesses were most exposed.

In retrospect, she was foolish. But in all fairness, how could she have known?

Abbie’s ex-husband had accused her of irreparable timidity, criticizing her for refusing to go snorkeling or even swimming with dolphins, never mind the scuba diving he’d loved since he was sixteen. The world was populated by water people and land people, and Abbie was firmly attached to terra firma. Until Graceville. And the lake.

Soon after she began her nightly wading, which gradually turned to dog-paddling and then awkward strokes across the dark surface, she began to dream about the water. Her dreams were far removed from her nightly dipping—which actually was somewhat timid, if she was honest. In sleep, she glided effortlessly far beneath the murky surface, untroubled by the nuisance of lungs and breathing. The water was a muddy green-brown, nearly black, but spears of light from above gave her tents of vision to see floating plankton, algae, tadpoles, and squirming tiny creatures she could not name . . . and yet knew. Her underwater dreams were a wonderland of tangled mangrove roots coated with algae, and forests of gently waving lily pads and swamp grass. Once, she saw an alligator’s checkered, pale belly above her, until the reptile hurried away, its powerful tail lashing to give it speed. In her dream, she wasn’t afraid of the alligator; she’d sensed instead (smelled instead?) that the alligator was afraid of her.

Abbie’s dreams had never been so vivid. She awoke one morning drenched from head to toe, and her heart hammered her breathless until she realized that her mattress was damp with perspiration, not swamp water. At least . . . she thought it must be perspiration. Her fear felt silly, and she was blanketed by sadness as deep as she’d felt the first months after her divorce.

Abbie was so struck by her dreams that she called Mary Kay, who kept dream diaries and took such matters far too seriously.

“You sure that water’s safe?” Mary Kay said. “No chemicals being dumped out there?”

“The water’s fine,” Abbie said, defensive. “I’m not worried about the water. It’s just the dreams. They’re so . . .” Abbie rarely ran out of words, which Mary Kay knew full well.

“What’s scaring you about the dreams?”

“The dreams don’t scare me,” Abbie said. “It’s the opposite. I’m sad to wake up. As if I belong there, in the water, and my bedroom is the dream.”

Mary Kay had nothing to offer except a warning to have the local Health Department come out and check for chemicals in any water she was swimming in, and Abbie felt the weight of her distance from her friend. There had been a time when she and Mary Kay understood each other better than anyone, when they could see past each other’s silences straight to their thoughts, and now Mary Kay had no idea of the shape and texture of Abbie’s life. No one did.

All liberation is loneliness, she thought sadly.

Abbie dressed sensibly, conservatively, for her first day at her new school.

She had driven the two miles to the school, a redbrick converted bank building in the center of downtown Graceville, before she noticed the itching between her toes.

“LaFleur,” the headmistress said, keeping pace with Abbie as they walked toward her assigned classroom for the course she’d named Creativity & Literature. The woman’s easy, Southern-bred tang seemed to add a syllable to every word. “Where is that name from?”

Abbie wasn’t fooled by the veiled attempt to guess at her ethnicity, since it didn’t take an etymologist to guess at her name’s French derivation. What Loretta Mill house really wanted to know was whether Abbie had ancestry in Haiti or Martinique to explain her sun-kissed complexion and the curly brown hair Abbie kept locked tight in a bun.

Abbie’s itching feet had grown so unbearable that she wished she could pull off her pumps. The itching pushed irritation into her voice. “My grandmother married a Frenchman in Paris after World War II,” she explained. “LaFleur was his family name.”

The rest was none of her business. Most of her life was none of anyone’s business.

“Oh, I see,” Mill house said, voice filled with delight, but Abbie saw her disappointment that her prying had yielded nothing. “Well, as I said, we’re so tickled to have you with us. Only one letter in your file wasn’t completely glowing . . .”

Abbie’s heart went cold, and she forgot her feet. She’d assumed that her detractors had remained silent, or she never would have been offered the job.

Mill house patted her arm. “But don’t you worry: Swimming upstream is an asset here.” The word “swimming” made Abbie flinch, feeling exposed. “We welcome in dependent thinking at Graceville Prep. That’s the main reason I wanted to hire you. Between you and me, how can anyone criticize a . . . creative mind?”

She said the last words conspiratorially, leaning close to Abbie’s ear as if a creative mind were a disease. Abbie’s mind raced: The criticism must have come from Johanssen, the vice principal at Blake who had labeled her argumentative—a bitch, Mary Kay had overheard him call her privately, but he wouldn’t have put that in writing. What did Mill house’s disclosure mean? Was Millhouse someone who pretended to compliment you while subtly putting you down, or was a shared secret hidden beneath the twinkle in her aqua-green eyes?

“Don’t go easy on this group,” Millhouse said when they reached room 113. “Every jock trying to make up a credit to stay on the roster is in your class. Let them work for it.”

Sure enough, when Abbie walked into the room, she faced desks filled with athletic young men. Graceville was a coed school, but only five of her twenty students were female.

Abbie smiled.

Her house would be fixed up sooner than she’d expected.

Abbie liked to begin with Thomas Hardy. Jude the Obscure. That one always blew their young minds, with its frankness and unconventionality. Their other instructors would cram conformity down their throats, and she would teach rebellion.

No rows of desks would mar her classroom, she informed them. They would sit in a circle. She would not lecture; they would have conversations. They would discuss the readings, read pages from their journals, and share poems. Some days, she told them, she would surprise them by playing music and they would write what ever came to mind.

Half the class looked relieved, the other half petrified.

During her orientation, Abbie studied her students’ faces and tried to guess which ones would be most useful over the summer. She dismissed the girls, as she usually did; most were too wispy and pampered, or far too large to be accustomed to physical labor.

* * *

But the boys. The boys were a different matter.

Of the fifteen boys, only three were unsuitable at a glance—bird-chested and reedy, or faces riddled with acne. She could barely stand to look at them.

That left twelve to ponder. She listened carefully as they raised their hands and described their hopes and dreams, watching their eyes for the spark of maturity she needed. Five or six couldn’t hold her gaze, casting their eyes shyly at their desks. No good at all.

Down to six, then. Several were basketball players, one a quarterback. Mill house hadn’t been kidding when she’d said that her class was a haven for desperate athletes. The quarterback, Derek, was dark-haired with a crater-sized dimple in his chin; he sat at his desk with his body angled, leg crossed at the knee, as if the desk were already too small. He didn’t say “uhm” or pause between his sentences. His future was at the tip of his tongue.

“I’m sorry,” she said, interrupting him. “How old did you say you are, Derek?”

He didn’t blink. His dark eyes were at home on hers. “Sixteen, ma’am.”

Sixteen was a good age. A mature age.

A female teacher could not be too careful about which students she invited to her home. Locker-room exaggerations held grave consequences that could literally steal years from a young woman’s life. Abbie had seen it before; entire careers up in fl ames. But this Derek . . .

Derek was full of possibilities. Abbie suddenly found herself playing Mill house’s game, noting his olive complexion and dark features, trying to guess if his jet-black hair whispered Native American or Hispanic heritage. Throughout the ninety-minute class, her eyes came to Derek again and again.

The young man wasn’t flustered. He was used to being stared at.

Abbie had made up her mind before the final bell, but she didn’t say a word to Derek. Not yet. She had plenty of time. The summer had just begun.

As she was climbing out of the shower, Abbie realized her feet had stopped their terrible itching. For three days, she’d slathered the spaces between her toes with creams from Walgreens, none helping, some only stinging her in punishment.

But the pain was gone.

Naked, Abbie raised her foot to her mattress, pulling her toes apart to examine them . . . and realized right away why she’d been itching so badly. Thin webs of pale skin had grown between her toes. Her toes, in fact, had changed shape entirely, pulling away from each other to make room for webbing. And weren’t her toes longer than she remembered?

No wonder her shoes felt so tight! She wore a size eight, but her feet looked like they’d grown two sizes. She was startled to see her feet so altered, but not alarmed, as she might have been when she was still in Boston, tied to her old life. New job, new house, new feet. There was a logical symmetry to her new feet that superseded questions or worries.

Abbie almost picked up her phone to call Mary Kay, but she thought better of it. What else would Mary Kay say, except that she should have had her water tested?

Instead, still naked, Abbie went to her kitchen, her feet slapping against her ugly kitchen flooring with unusual traction.

When she brushed her upper arm carelessly across her ribs, new pain made her hiss. The itching had migrated, she realized.

She paused in the bright fluorescent lighting to peer down at her rib cage and found her skin bright red, besieged by some kind of rash. Great, she thought. Life is an endless series of challenges. She inhaled a deep breath, and the air felt hot and thin. The skin across her ribs pulled more tautly, constricting. She longed for the lake.

Abbie slipped out of her rear kitchen door and scurried across her backyard toward the black shimmer of the water. She’d forgotten her flip-flops, but the soles of her feet were less tender, like leather slippers.

She did not hesitate. She did not wade. She dove like an eel, swimming with an eel’s ease. Am I truly awake, or is this a dream?

Her eyes adjusted to the lack of light, bringing instant focus. She had never seen the true murky depths of her lake, so much like the swamp of her dreams. Were they one and the same? Her ribs’ itching turned to a welcome massage, and she felt long slits yawn open across her skin, beneath each rib. Warm water flooded her, nursing her; her nose, throat, and mouth were a useless, distant memory. Why hadn’t it ever occurred to her to breathe the water before?

An alligator’s curiosity brought the beast close enough to study her, but it recognized its mistake and tried to thrash away. But too late. Too late. Nourished by the water, Abbie’s instincts gave her enough speed and strength to glide behind the beast, its shadow. One hand grasped the slick ridges of its tail, and the other hugged its wriggling girth the way she might a lover. She didn’t remember biting or clawing the alligator, but she must have done one or the other, because the water fl owed red with blood.

The blood startled Abbie awake in her bed, her sheets heavy with dampness. Her lungs heaved and gasped, shocked by the reality of breathing, and at first she seemed to take in no air. She examined her fi ngers, nails, and naked skin for blood, but found none. The absence of blood helped her breathe more easily, her lungs freed from their confusion.

Another dream. Of course. How could she mistake it for anything else?

She was annoyed to realize that her ribs still bore their painful rash and long lines like raw, infected incisions.

But her feet, thank goodness, were unchanged. She still had the delightful webbing and impressive new size, longer than in her dream. Abbie knew she would have to dress in a hurry. Before school, she would swing by Payless and pick up a few new pairs of shoes.

Derek lingered after class. He’d written a poem based on a news story that had made a deep impression on him; a boy in Naples had died on the football practice field. Before he could be tested by life, Derek had written in his eloquent final line. One of the girls, Riley Bowen, had wiped a tear from her eye. Riley Bowen always gazed at Derek as if he were the answer to her life’s prayers, but he never looked at her.

And now here was Derek standing over Abbie’s desk, on his way to six feet tall, his face bowed with shyness for the first time all week.

“I lied before,” he said, when she waited for him to speak. “About my age.”

Abbie already knew. She’d checked his records and found out for herself, but she decided to torture him.”Then how old are you?”

“Fifteen.” His face soured. “Till March.”

“Why would you lie about that?”

He shrugged, an adolescent gesture that annoyed Abbie no end.

“Of course you know,” she said. “I heard your poem. I’ve seen your thoughtfulness. You wouldn’t lie on the fi rst day of school without a reason.”

He found his confidence again, raising his eyes. “Fine. I skipped second grade, so I’m a year younger than everyone in my class. I always say I’m sixteen. It wasn’t special for you.”

The fight in Derek intrigued her. He wouldn’t be the type of man who would be pushed around. “But you’re here now, baring your soul. Who’s that for?”

His face softened to half a grin. “Like you said, when we’re in this room, we tell the truth. So here I am. Telling the truth.”

There he was. She decided to tell him the truth, too.

“I bought a big house out by the lake,” she said. “Against my better judgment, maybe.”

“That old one on McCormack Road?”

“You know it?”

He shrugged, that loathsome gesture again. “Everybody knows the McCormacks. She taught Sunday school at Christ the Redeemer. Guess she moved out, huh?”

“To her sister’s in . . . Quincy?” The town shared a name with the city south of Boston, the only reason she remembered it. Her mind was filled with distraction to mask strange flurries of her heart. Was she so cowed by authority that she would leave her house in a mess?

“Yeah, Quincy’s about an hour, hour and a half, down the Ten . . .” Derek was saying in a flat voice that bored even him.

They were talking about nothing. Waiting. They both knew it.

Abbie clapped her hands once, snapping their conversation from its trance. “Well, an old house brings lots of problems. The porch needs fixing. New kitchen tiles. I don’t have the bud get to hire a real handyman, so I’m looking for people with skills . . .”

Derek’s cheeks brightened, pink. “My dad and I built a cabin last summer. I’m pretty good with wood. New planks and stuff. For the porch.”

“Really?” She chided herself for the girlish rise in her pitch, as if he’d announced he had scaled Mount Everest during his two weeks off from school.

“I could help you out, if . . . you know, if you buy the supplies.”

“I can’t pay much. Come take a look after school, see if you think you can help.” She made a show of glancing toward the open doorway, watching the stream of students passing by.”But you know, Derek, it’s easy for people to get the wrong idea if you say you’re going to a teacher’s house . . .”

His face was bright red now. “Oh, I wouldn’t say nothing. I mean . . . anything. Besides, we go fishing with Coach Reed all the time. It’s no big deal around here. Not like in Boston, maybe.” The longer he spoke, the more he regained his poise. His last sentence had come with an implied wink of his eye.

“No, you’re right about that,” she said, and she smiled, remembering her new feet. “Nothing here is like it was in Boston.”

That was how Derek Voorhoven came to spend several days a week after class helping Abbie fix her ailing house, whenever he could spare time after football practice in the last daylight. Abbie made it clear that he couldn’t expect any special treatment in class, so he would need to work hard on his atrocious spelling, but Derek was thorough and uncomplaining. No task seemed too big or small, and he was happy to scrub, sand, and tile in exchange for a few dollars, conversation about the assigned reading, and fishing rights to the lake, since he said the catfi sh favored the north side, where it was quiet.

As he’d promised, he told no one at Graceville Prep, but one day he asked if his cousin Jack could help from time to time, and after he’d brought the stocky, freckled youth by to introduce him, she agreed. Jack was only fourteen, but he was strong and didn’t argue. He also attended the public school, which made him far less a risk. Although the boys joked together, Jack’s presence never slowed Derek’s progress much, so Derek and Jack became fixtures in her home well into July. Abbie looked forward to fixing them lemonade and white chocolate macadamia nut cookies from ready-made dough, and with each passing day she knew she’d been right to leave Boston behind.

Still, Abbie never told Mary Kay about her visits with the boys and the work she asked them to do. Her friend wouldn’t judge her, but Abbie wanted to hold her new life close, a secret she would share only when she was ready, when she could say: You’ll never guess the clever way I got my improvements done, an experience long behind her. Mary Kay would be envious, wishing she’d thought of it first, rather than spending a fortune on a gardener and a pool boy.

But there were other reasons Abbie began erecting a wall between herself and the people who knew her best. Derek and Jack, bright as they were, weren’t prone to notice the small changes, or even the large ones, that would have leaped out to her mother and Mary Kay—and even her distracted father.

Her mother would have spotted the new size of her feet right away, of course. And the odd new pallor of her face, fishbelly pale. And the growing strength in her arms and legs that made it so easy to hand the boys boxes, heavy tools, or stacks of wooden planks. Mary Kay would have asked about the flaky skin on the back of her neck and her sudden appetite for all things rare, or raw. Abbie had given up most red meat two years ago in an effort to remake herself after the divorce tore her self-esteem to pieces, but that summer she stocked up on thin-cut steaks, salmon, and fish she could practically eat straight from the packaging. Her hunger was also voracious, her mouth watering from the moment she woke, her growling stomach keeping her awake at night.

She was hungriest when Derek and Jack were there, but she hid that from herself.

Her dusk swims had grown to evening swims, and some nights she lost track of time so completely that the sky was blooming pink by the time she waded from the healing waters to begin another day of waiting to swim. She resisted inviting the boys to swim with her.

The last Friday in July, with only a week left in the summer term, Abbie lost her patience.

She was especially hungry that day, dissatisfied with her kitchen stockpile. Graceville was suffering a record heat wave with temperatures hovering near 110 degrees, so she was sweaty and irritable by the time the boys arrived at five thirty. And itching terribly. Unlike her feet, the gills hiding beneath the ridges of her ribs never stopped bothering her until she was in her lake. She was so miserable, she almost asked the boys to forget about painting the refurbished back porch and come back another day.

If she’d only done that, she would have avoided the scandal.

Abbie strode behind the porch to watch the strokes of the boys’ rollers and paintbrushes as they transformed her porch from an eyesore to a snapshot of the quaint Old South. Because of the heat, both boys had taken their shirts off, their shoulders ruddy as the muscles in their sun-broiled backs flexed in the Magic Hour’s furious, gasping light. They put Norman Rockwell to shame; Derek with his disciplined football player’s physique, and Jack with his awkward baby fat, sprayed with endless freckles.

“Why do you come here?” she asked them.

They both stopped working, startled by her voice.

“Huh?” Jack said. His scowl was deep, comical. “You’re paying us, right?”

Ten dollars a day each was hardly pay. Derek generously shared half of his twenty dollars with his cousin for a couple hours’ work, although Jack talked more than he worked, running his mouth about summer superhero blockbusters and dancers in music videos. Abbie regretted that she’d encouraged Derek to invite his cousin along, and that day she wished she had a reason to send Jack home. Her mind raced to come up with an excuse, but she couldn’t think of one. A sudden surge of frustration pricked her eyes with tears.

“I’m not paying much,” she said.

“Got that right,” Derek said. Had his voice deepened in only a few weeks? Was Derek undergoing changes, too? “I’m here for the catfish. Can we quit in twenty minutes? I’ve got my rod in the truck. And some chicken livers I’ve been saving.”

“Quit now if you want,” she said. She pretended to study their work, but she couldn’t focus her eyes on the whorls of painted wood. “Go on and fish, but I’m going swimming. Good way to wash off a hot day.”

She turned and walked away, following the familiar trail her feet had beaten across her backyard’s scraggly patch of grass to the strip of sand. She’d planned to lay sod with the boys closer to fall, but that might not happen now.

Abbie pulled off her T-shirt, draping it nonchalantly across her beach lounger, taking her time. She didn’t turn, but she could feel the boys’ eyes on her bare back. She didn’t wear a bra most days; her breasts were modest, so what was the point? One more thing Johanssen had tried to hold against her. Her feet curled into the sand, searching for dampness.

“It’s all right if you don’t have trunks,” she said. “My backyard is private, and there’s no harm in friends taking a swim.”

She thought she heard them breathing, or maybe the harsh breaths were hers as her lungs prepared to give up their reign. The sun was unbearable on Abbie’s bare skin. Her sides burned like fire as the flaps beneath her ribs opened, swollen rose petals.

The boys didn’t answer; probably hadn’t moved. She hadn’t expected them to, at first.

One after the other, she pulled her long legs out of her jeans, standing at a discreet angle to hide most of her nakedness, like the Venus de’ Medici. She didn’t want them to see her gills, or the rougher patches on her scaly skin. She didn’t want to answer questions. She and the boys had spent too much time talking all summer. She wondered why she’d never invited them swimming before.

She dove, knowing just where the lake was deep enough not to scrape her at the rocky floor. The water parted as startled catfish dashed out of her way. Fresh fish was best. That was another thing Abbie had learned that summer.

When her head popped back up above the surface, the boys were looking at each other, weighing the matter. Derek left the porch first, tugging on his tattered denim shorts, hopping on one leg in his hurry. Jack followed but left his clothes on, arms folded across his chest.

Derek splashed into the water, one polite hand concealing his privates until he was submerged. He did not swim near her, leaving a good ten yards between them. After a tentative silence, he whooped so loudly that his voice might have carried across the lake.

“Whooo-hooooo!” Derek’s face and eyes were bright, as if he’d never glimpsed the world in color before. “Awesome!”

Abbie’s stomach growled. She might have to go after those catfish. She couldn’t remember being so hungry. She felt faint.

Jack only made it as far as the shoreline, still wearing his Bermuda shorts. “Not supposed to swim in the lake in summer,” he said sullenly, his voice barely loud enough to hear. He slapped at his neck. He stood in a cloud of mosquitoes.

Derek spat, treading water. “That’s little kids, dumbass.”

“Nobody’s supposed to,” Jack said.

“How old are you, six? You don’t want to swim—fine. Don’t stand staring. It’s rude.”

Abbie felt invisible during their exchange. She almost told Jack he should follow his best judgment without pressure, but she dove into the silent brown water instead. Young adults had to make decisions for themselves, especially boys, or how would they learn to be men? That was what she and Mary Kay had always believed. Anyone who thought differently was just being politically correct. In ancient times, or in other cultures, a boy Jack’s age would already have a wife, a child of his own.

Just look at Mary Kay. Everyone had said her marriage would never work, that he’d been too young when they met. She’d been vilified and punished, and still they survived. The memory of her friend’s trial broke Abbie’s heart.

As the water massaged her gills,Abbie released her thoughts and concerns about the frivolous world beyond the water. She needed to feed, that was all. She planned to leave the boys to their bickering and swim farther out, where the fish were hiding.

But something large and pale caught her eye above her.

Jack, she realized dimly. Jack had changed his mind, swimming near the surface, his ample belly like a full moon, jiggling with his breast stroke.

That was the first moment Abbie felt a surge of fear, because she finally understood what she’d been up to—what her new body had been preparing her for. Her feet betrayed her, their webs giving her speed as she propelled toward her giant meal. Water slid across her scales.

The beautiful fireball of light above the swimmer gave her pause, a reminder of a different time, another way. The tears that had stung her in her backyard tried to burn her eyes blind, because she saw how it would happen, exactly like a dream: She would claw the boy’s belly open, and his scream would sound muffled and faraway to her ears. Derek would come to investigate, to try to rescue him from what he would be sure was a gator, but she would overpower Derek next. Her new body would even if she could not.

As Abbie swam directly beneath the swimmer, bathed in the magical light fighting to shield him, she tried to resist the overpowering scent of a meal and remember that he was a boy. Someone’s dear son. As Derek (was that the other one’s name?) had put it so memorably some time ago—perhaps while he was painting the porch, perhaps in one of her dreams—neither of them yet had been tested by life.

But it was summertime. In Graceville.

In the lake.

“The Lake” copyright © 2011 Tananarive Due